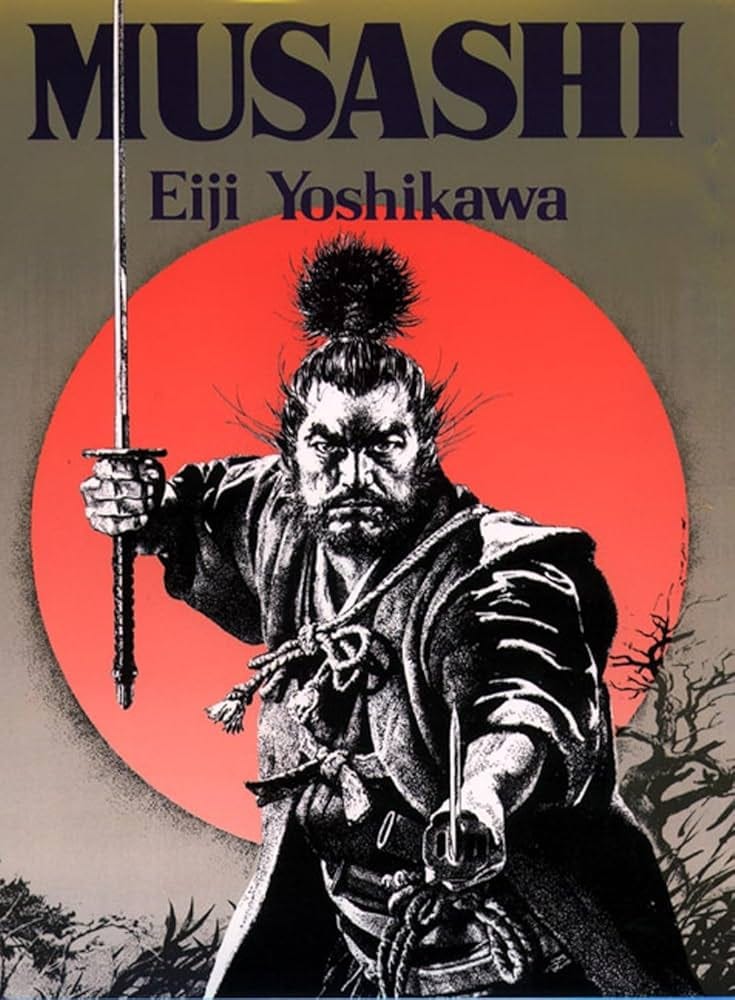

Musashi by Eiji Yoshikawa is a masterpiece. I’ve used it along with many of my smartest friends to calibrate lessons on discernment, leadership, and self-awareness.

I want to share some of my favorite learnings from the book with other fans and encourage people who’ve read it to look more deeply at it, or people who are considering it to read it.

The best way to introduce what Yoshikawa has accomplished in the novel is by using a metaphor of his about the nature of expertise and perception, expressed as Musashi considers a ceramic piece by master craftsman Hon'ami Koetsu:

[Musashi] reached out, picked up the bowl lovingly and placed it on his knee. His eyes shone as he examined it; he felt an excitement he had never experienced before. As he studied the bottom of the vessel and the traces of the potter’s spatula, he realized that the lines had the same keenness as Sekishusai’s slicing of the peony stem. This unpretentious bowl, too, had been made by a genius. It revealed the touch of the spirit, the mysterious insight. …

What affected him more than the man’s artistic versatility, however, was the human profundity concealed within this ostensibly plain tea bowl. It disturbed him a little to recognize the depth of Koetsu’s spiritual resources. Accustomed to measuring men in terms of their swordsmanship, he suddenly decided that his yardstick was too short. The thought humbled him; here was yet another man before whom he must admit defeat.

The novel is a masterpiece in the same way – at first glance it might appear mundane, but upon closer examination, the genius reveals itself.

Musashi works on many levels, meeting the reader where they are. If you want to enjoy the adventure novel, there’s action and romance; like the tea bowl, you can enjoy its superficial function without appreciating it more deeply than that.

But the details in Yoshikawa’s finer strokes communicate deep truths about perception and how individuals’ philosophical orientations determine their paths through life, and how those choices affect others.

More than that, he constructs a coherent, accurate, and above all useful model of the world as it is based on deep insight into character and societal institutions.

The novel follows Miyamoto Musashi and a handful of individuals in his orbit across about twelve years of story time; long enough for Yoshikawa to demonstrate how personal choices influence individual and institutional trajectories, which in aggregate come to comprise society.

Over the course of the novel, we see Musashi transform from a rough and callow youth to a great samurai; his old friend and once peer Honiden Matahachi from a promising young man to a wayward soul; rival swordsman Sasaki Kojiro from a hungry prodigy to an amoral but successful retainer.

Akemi’s unlucky upbringing sets her down a troubled path. Otsu uses her moral strength in the service of others. Takuan expands his powers in his chosen vocation. Tanzaemon faces setbacks in midlife. Sekishusai works to pass along the flame of civilization that he received from his mentor Koizumi.

The once-proud Yoshioka School collapses under its own mismanagement and inability to face reality; the quietly competent Yagyu family rises from a well-managed local faction to excellence at the side of the Shogun. The Obata School makes the wrong enemy and is crushed. Tadaaki’s attempt at institution-building fails. Retainers’ fortunes rise and fall.

Why? And – so what?

Yoshikawa suggests that most people waste the gift of being born human, spending their lives wrapped in illusion and warped by expectation. His exhortation

The world is always full of the sound of waves. The little fishes, abandoning themselves to the waves, dance and sing and play, but who knows the heart of the sea, a hundred feet down? Who knows its depth?

echoes Matthew 7:13 –

Enter through the narrow gate; for the gate is wide and the way is broad that leads to destruction, and there are many who enter through it. For the gate is small and the way is narrow that leads to life, and there are few who find it.

The world of Musashi explores that distinction with relatable human scenes and characters. Most people march merrily enough down the broad way. The people who are truly admirable – not just worthy of compassion, but admiration and emulation – do something else.

Fortunately for us, Yoshikawa uses Musashi’s 970 pages to help us feel that distinction for ourselves.

Yoshikawa uses an omniscient, third-person, impartial narrator to show us the internal states and motivations of characters both directly and in the selection of specific, often subtly presented key details. What characters perceive, or fail to perceive, based on their goals and orientations toward reality determines how their stories turn out.

This mechanism drives the novel’s transformative power: we as readers can relate and track our own thinking and self-narrative against the characters and find both aspirational and cautionary patterns.

We primarily follow Musashi himself and encounter the characters that he crosses paths with along his journey toward growth and mastery. The characters we meet early in the book show us the impact of different philosophies; later, the interplay of different groups in society; and by the end, tracking Musashi’s own development, different approaches to leadership and governance.

Beneath the adventure, the novel explores what to expect along the path to becoming established in society and making a positive contribution.

So what is Yoshikawa telling us about life?

Your life depends on how you direct your attention.

Musashi finds the right orientation in his youth thanks to the opportunity the priest Takuan creates for him to study the Art of War and other classics that provide the foundation for his life philosophy.

By the time Musashi leaves Lord Terumasa’s captivity, he’s decided to pursue the highest good and each of his subsequent actions and perceptions are attuned to helping him take the next step on that path.

“Takuan follows the Way of Zen, I will follow the Way of the Sword. I must make of myself an even better man than he is.” …

His footsteps were steady and strong, his eyes full of youth and hope. From time to time he raised the brim of his basket hat, and stared down the long road into the future, the unknown path all humans must tread.

Matahachi never has a moment like this – he chooses short-term thinking and lust, and this degrades his character throughout the rest of the novel. He never anchors himself to a philosophy: “it seemed to Matahachi that the world was a vast, turbulent sea on which there was nothing to cling to,” and by default he seeks to preserve his ego at the expense of higher values.

The difference starts out innocuously enough but compounds over time, tragically in Matahachi’s case. A once-promising young heir of a household – with great prospects and a beautiful fiancée through no skill of his own – Matahachi makes one mistake then another, unable to perceive the depth of his errors because he doesn’t have an aim.

Matahachi falls into delusion, depression, and struggle, and Yoshikawa shows us the mental process this deconstruction follows. At first he expects more of himself, calling back memories of poetry he learned as a cultivated youth, but eventually buries his aspirations under resentment, a Cain-like figure taking indefensible shortcuts to cheat his way to prestige because he can’t face the reality of who he’s become.

Other characters’ thoughts and perceptions reflect their driving orientations, though few choose to pursue the highest good. Osugi is oriented toward pride, and sees every possibility available to her as either advancing her pride or not. Kojiro is oriented to power, and treats the lives of others as stepping-stones unworthy of consideration beyond how they support his pursuit.

By the time Matahachi crosses paths with Musashi again, the two men, once peers, are incomprehensible to each other. Musashi built his identity around his pursuit of mastery and doesn’t understand Matahachi’s struggles; he’s constructed his mind such that the challenges Matahachi is facing are completely alien concepts.

Matahachi no doubt meant well, but there was something twisted about his attitude. Why must he praise Musashi so and in the next breath carry on so about his own failings? “Why,” wondered Musashi, “couldn’t he just write and say that it’s been a long time, and why don’t we get together and have a long talk?”

Where Matahachi’s inner monologue is filled with angst and regret, Musashi’s is focused on ways to improve, and over time the difference is undeniable. Hardships build Musashi up but break Matahachi down – because only Musashi had the wisdom or good fortune to intentionally choose his life philosophy.

Perceptiveness is the key to personal growth and mastery.

All of the most impressive characters in Musashi have perceptual abilities that appear supernatural to the average person, if they’re aware of them at all – but are really the result of careful cultivation.

Musashi himself is the reader’s stand-in for developing this capability. Yoshikawa is clear that at the start of the novel, the young Takezo is strong and energetic, but not particularly discerning.

It’s only after he has familiarized himself with the Art of War and set his intention on mastery that he gains the ability to learn from experience. Once he does, he finds opportunities everywhere, and we can follow his growth by the new levels of awareness that open up to him.

His encounter with the abbot Nikkan of the Ozoin is his first realization that others are able to detect things in him that he isn’t aware are perceptible – his strength and belligerence cause people to react to him with hostility, and Nikkan does him a huge favor by calling this out.

When Musashi and his young ward Jotaro enter Koyagyu, governed by the wise Yagyu Sekishusai and his retainers, Musashi infers details about the health of the society from seemingly superficial details like the trees and the looks of the villagers.

“All the trees in Yagyu are old. That means there haven’t been any wars here, no enemy troops burning or cutting down the forests. It also means there haven’t been any famines, at least for a long, long time. …

Listen! Can’t you hear the sound of spinning wheels? It seems to be coming from every house. And haven’t you noticed that when travelers in fine clothing pass by, the farmers don’t look at them enviously? …

The children are growing up healthy, the old people are treated with due respect, and the young men and women aren’t running off to live uncertain lives in other places. It’s a safe bet that the lord of the district is wealthy, and that the swords and guns in his armory are kept polished and in the best condition.”

Later, we see how masters use perceptiveness to operate politically. Yagyu Sekishusai cuts a peony stem to see if Denshichiro from the Yoshioka school knows enough about good swordsmanship to recognize his work. When Denshichiro misses the signal, Sekishusai accurately updates his perception of the Yoshiokas without putting himself or his interests at risk.

Musashi doesn’t see the context behind what Sekishusai – probably the greatest master we see at work in the novel – is doing here, but he does notice the cut, and it helps him discern the gaps in his own skill and calibrate appropriately. Then, this encounter with mastery enables him to perceive the expertise with which Hon’ami Koetsu crafts his pottery.

There’s a running theme in the novel that great fighters can size each other up instantly and masters know the outcome of fatal duels before they happen. Kojiro knows that Musashi will defeat Yoshioka Seijuro; Musashi knows Kojiro will defeat Obata Yogoro; Nikkan tries in vain to warn Agon, the Hozoin champion lancer, off of dueling Musashi knowing he’d lose.

In light of this, one of the funniest parts of the book is when Matahachi psyches himself up to fight Kojiro in direct contrast to everything we know about both characters. It doesn’t go as badly as it could for Matahachi – they don’t end up fighting – but it goes to show the importance of perceptiveness and the ability to wisely pick your battles.

Musashi eventually becomes so perceptive that he’s able to sense subtle traps. He knows that Yagyu Munenori is waiting in a mock ambush and wisely avoids crossing his path, demonstrating his prowess while saving both men the danger and potential embarrassment of a confrontation.

“The truth is that although I’ve heard what sort of man you are, I had no way of knowing just how well trained and disciplined you are. I thought I’d see for myself…. But you perceived you were being lured into a trap and came across the garden. May I ask why you did that?”

Musashi merely grinned.

Musashi’s discernment is a major source of his power throughout the novel. His capability to anticipate martial and political dynamics becomes increasingly astute and calibrated; this enables him to operate effectively at higher levels of society, cause less destruction and chaos, and face less personal risk.

Notably, his mastery in those matters doesn’t extend to the romantic realm. In exactly the way he would never underestimate an opponent, Musashi wrongly anticipates that his beloved Otsu will wait until morning to set off on the road in response to a letter of his, but she leaves as soon as she receives the note at dusk.

Reputation isn’t reality; don’t form second-hand opinions.

Yoshikawa gives no credence to public opinion. He disdains the masses as a mob, blinded by prestige, quick to change, and keen to follow any kind of gossip or agitation.

Musashi stared on in silence, his mind in a quandary.

“Look at the bastard! He’s afraid!” a porter shouted.

“Be a man! Let the old woman kill you!” taunted another.

There was not a soul who was not on Osugi’s side.

By showing us the inner workings of several institutions and how public opinion is molded, Yoshikawa encourages us to avoid getting caught up in judgments or emotional responses where we don’t have personal first-hand experience.

Combative partisans regularly put up sign-boards advertising the virtues of their schools and smearing their opponents as cowards, regardless of the true merits of either party; but this is enough to establish conventional wisdom unless and until there’s an actual fight.

Osugi spends most of the novel spreading calumnies about Musashi, either outright lies or stories calibrated to paint him in the worst light possible, and these stories do real damage to Musashi’s relationships and prospects.

In contrast, we see the more PR-savvy Kojiro’s reputation rise over the course of the novel, even though he’s regularly picking fights and killing people on flimsy pretenses.

It’s only after Musashi helps rescue a village by rallying the people to repel a gang of bandits that Tadatoshi’s retainer Sado sees Musashi’s character for himself.

Though external perception and reputation don’t map to reality, there are signs of genuine strength and weakness for the discerning observer. Yoshikawa’s introduction to the Yoshioka School tells us everything we need to know, even before we see the dysfunction of their key players:

A wooden plaque, blackened with age, announced in barely legible writing: “Yoshioka Kempō of Kyoto. Military Instructor to the Ashikaga Shōguns.”

By showing us the internal politics of the Yoshioka organization – declining discipline, frivolous spending, jockeying for rank, taking any operational criticism as disloyalty – we see how a prestigious, proud school rots from the inside out while it enjoys the reputation earned from past performance until its eventual irrevocable collapse.

The Yagyu organization doesn’t seek prestige at all, and maintains focus on its core functions of effective training and governance. They wisely avoid attention and their reputation doesn’t reflect their institutional capability. Musashi has to go to Koyagyu, walk around, and meet their samurai to get a sense of how strong they really are.

We see enough of the Yoshioka and Yagyu institutions and their contrasting reputations to know that we aren’t in position to judge anyone else from a distance; though we hear about the power struggle for top leadership, it’s beyond any of the characters’ locus of control and would be foolish for them or us to speculate on.

Instead of chasing prestige, find other seekers of the Way.

While the structure and legibility of institutions make joining up appealing to people looking to get ahead in society, Yoshikawa calls out the dynamics that can make joining an institution dangerous, especially for those seeking mastery.

You might join an institution that is externally prestigious, but actually dysfunctional. You might join an institution that isn’t as good as others, locking into a second-rate style and limiting your development. In either case, the need to defend your group and its approach warps your ability to view your situation objectively.

Even if you join a well-led institution and rise along with it, your attention will be somewhat diverted to court politics and responsibilities. Good faith participation in an institution means you take on its goals and obligations as your own in exchange for access to its platform.

We see devoted partisans caught up in skirmishes and vendettas that were caused by misadventures or misunderstandings, who have to risk their lives because of a perceived slight. It’s a dangerous world, and their honor demands following through even if it’s ill-advised to do so.

“After he dragged our master’s name through the mud? After he killed four of our men? You keep saying we’re not being reasonable. Aren’t you the one who’s lost his reason? Controlling your temper, holding yourself back, bearing insults in silence. Is that what you call reasonable? That’s not the Way of the Samurai.”

Even with these risks, most people are better off within the system than outside of it. Institutions like the well-run Yagyu or Hosokawas provide stability, mentorship, and opportunities for meaningful contribution. Even flawed institutions offer more structure and support than the precarious path of the masterless ronin.

Yoshikawa offers an alternative that might seem idealistic, but also demonstrates the mechanics by which it can and does work in practice: instead of following an institutional path, seeking fellowship with others pursuing excellence.

The bar for success here is high, and in the novel, the only character to pursue this path from its first steps is Musashi. His first encounter with a fellow Way-seeker is with Takuan, who helps him find his footing; but it’s only after his encounter with Hon’ami Koetsu that he realizes that the Way goes beyond combat and extends to mastery in any domain.

With Takuan and Koetsu as allies, Musashi becomes more refined in his pursuit of excellence, and his horizons expand. His fellowship with these masters leads him to other allies like the sword polisher Kosuke, and sets him up for more formal introductions into society as his powers increase.

Along the way, Musashi learns everything he can from top practitioners within different schools and lineages. He honors their accomplishments while cultivating his own discernment.

Self-discipline is the key to making this work; Matahachi is also outside of institutional structure, but things don’t go the same for him.

Eventually, Musashi finds his way to greater opportunity than would have been available to anyone who had taken a traditional path in the same time frame – introduced by Takuan and Lord Ujikatsu to Yagyu Munenori, whose “status was so far above Musashi’s as to put him virtually in another world. … To most people, it would have seemed odd to find one of the shogun’s tutors in the same room with Musashi, let alone talking to him in a friendly, informal fashion.”

Musashi knew he was being accepted in this select circle not because of who he was. He was seeking the Way, just as they were. It was the Way that permitted such free camaraderie.

As a result of the preparation and cultivation that preceded this meeting, Musashi was recommended as a tutor to the shogun – an honor that would represent an unthinkable jump in social standing.

A more familiar equivalent of this might be a self-taught lawyer who passes the Bar and demonstrates such merit, effectiveness, and clarity of thought in small-time private practice that they’re nominated for the U.S. Supreme Court.

While that’s an unlikely example today, there’s truth in the broader lesson. Disciplined pursuit of mastery creates opportunity without the need for compromise.

Try to avoid mistakes, but there’s grace when you need it.

Yoshikawa adds a depth of humanity and authenticity to the novel by taking us through episodes where characters, including Musashi, navigate painful setbacks caused by their own errors.

It isn’t enough to be oriented toward the highest good. You should expect to make mistakes along the way, and you might even lose faith for a while, that’s normal too. Musashi’s path to greatness includes reversals without damaging his essential character.

“If I desert the Way, I fall into the depths. Yet when I try to pursue it to the peak, I find I’m not up to the task. I’m twisting in the wind halfway up, neither the swordsman nor the human being I want to be.”

“That seems to sum it up.”

“You don’t know how desperate I’ve been. What should I do? Tell me! How can I free myself from inaction and confusion?”

“Why ask me? You can only rely on yourself.”

Not everyone in the novel is so lucky. The world of Musashi can be unforgiving. Some characters stay stuck in destructive patterns for too long and end up as a shell of their potential. Others, like the well-intentioned Obata Yogoro, pick the wrong opponent and lose a fatal duel in an instant. It’s important to discern what kind of mistakes are survivable and avoid the other kind.

It takes time for non-fatal mistakes and errors in judgment to catch up to most characters; just because disaster hasn’t arrived yet doesn’t mean it isn’t on the way. Matahachi misspent his youth, but didn’t hit rock bottom and begin to potentially turn things around until his encounter with Takuan over a decade after Musashi’s.

Aoki Tanzaemon spent his early career focused on performing the duties of a soldier, ignorant of morality and virtue. When he’s stripped of his rank, he loses the only identity he’d ever known, leaving him with anguish, regret, and the dashed hopes of an aging failure. But he reconstructs his character over the course of the novel, reclaiming a place in society and becoming a positive presence for his son Aoki Jotaro.

Even Osugi eventually sees the error of her ways after spending years on a misguided quest to get revenge on Musashi and Otsu. She’s eventually won over by Otsu’s strength and finally lets go of her anger and bitterness. It’s never too late to escape delusion, though it doesn’t erase the damage done along the way.

Past mistakes might come back to haunt you at inconvenient times. Musashi’s proposed appointment as a tutor to the shogun is derailed by Osugi’s campaign against his reputation. Although we know she’s misinterpreting his character, there’s enough truth in how she describes his reckless youth to block the appointment.

When you’re truly oriented toward the highest good, though, reversals like that are easy to move past. You aren’t dependent on external validation or outcomes to give your life meaning.

Musashi even demonstrates how to deal with unexpected setbacks: rather than being angry, blaming others or even dwelling on his past mistakes, he leaves behind a painting to prove his character and save face for the people who backed him, demonstrating grace where outside observers might reasonably expect frustration.

Sakai Tadakatsu returned to the waiting room and sat for some time gazing at the still damp painting. The picture was of Musashino Plain. In the middle, appearing very large, was the rising sun. This, symbolizing Musashi’s confidence in his own integrity, was vermilion. The rest of the work was executed in ink to capture the feeling of autumn on the plain. Tadakatsu said to himself, “We’ve lost a tiger to the wilds.”

Musashi is resilient, but has moments of self-doubt. Yoshikawa includes a curious chapter late in the book in which we follow Musashi through a spiritual crisis where he questions his path and even envies Matahachi.

It doesn’t advance the novel’s plot, so why include it? My sense is it’s a gift from Yoshikawa to readers, making Musashi’s character more relatable and walking us through the steps to get back on track when we experience the inevitable winters of life.

Embrace the impact your choices have on others.

Yoshikawa shows us that our choices ripple outward in ways we can’t fully imagine, affecting our own lives, those around us and generations to come. The cascading consequences of our own and others’ decisions, produced by their skills and perceptions, make up the world as we know it.

Yoshioka Kempo built a remarkable institution, but his failure to prepare his sons to work together in leading it didn’t just doom them, it destroyed the livelihoods of everyone dependent on the school.

Yagyu Sekishusai’s earnest transmission of Lord Koizumi’s wisdom created a multi-generational tradition of excellence, leading to greater influence in government and shaping the peace and prosperity of countless lives.

In Sekishusai’s view, the Art of War was certainly a means of governing the people, but it was also a means of controlling the self. This he had learned from Lord Koizumi, who, he was fond of saying, was the protective deity of the Yagyu household.

The stakes of these decisions are cosmic. Good governance creates conditions for flourishing, as we see in Koyagyu. Poor leadership breeds chaos and suffering, visible in territories where bandits roam freely and families make their living selling fallen soldiers’ weapons and armor.

Though we’re each born into a web of consequences, we can be intentional about our own legacy, wherever we find ourselves now and regardless of what’s happened in the past.

Musashi’s recklessness in his village as Takezo reverberates years later. Matahachi’s abandonment of his responsibilities devastates his family. But positive actions compound too – Takuan’s intervention with Takezo creates Musashi, whose example inspires countless others.

Yoshikawa shows us how a small number of people, dedicated to the Way, can have an outsized impact on their society’s flourishing. People who work and build with an eye toward the future, to being good ancestors and effective conduits of wisdom, can set the example for those who succeed them to follow their example and thrive.

“They say that by planting one seed of enlightenment you can convert a hundred people, and if one sprout of enlightenment grows in a hundred hearts, ten million souls can be saved.”

The fact that we’re still discussing Musashi centuries after he lived, and decades after Yoshikawa wrote, proves his point and speaks to his genius. The accumulation of our daily choices, felt and seen who we become and the legacies we leave behind, shape the world.

Engaging with Musashi is to experience its central lesson: developing discernment is a lifelong practice, and what we’re able to perceive depends on who we’ve become. As we grow and change, so does our ability to recognize the mastery in Yoshikawa’s work and apply its lessons in our own lives.

“I wouldn’t call Musashi ordinary.”

“But he is. That’s what’s extraordinary about him. He’s not content with whatever natural gifts he may have. Knowing he’s ordinary, he’s always trying to improve himself. No one appreciates the agonizing effort he’s had to make. Now that his years of training have yielded such spectacular results, everybody’s talking about his ‘god-given talent.’ That’s how men who don’t try very hard comfort themselves.”

Last quote hits hard. Thank you for writing!